December 4, 2025 at 7:51 pm | Updated December 4, 2025 at 7:51 pm | 9 min read

- Root senescence is typically an age-related process, although stress can lead to premature root decay.

- Root senescence occurs through programmed cell death, which is regulated by controls, some specific to roots and some common with leaf senescence.

- Root senescence occurs at different times across root types, and its progression depends on plant type.

Leaf senescence is the most recognized form of plant organ senescence, followed by flower senescence. However, root senescence also occurs; however, as with other belowground processes, it is less well understood. Modern imaging and root phenotyping, combined with advanced analysis, are helping to understand the importance of root senescence in plant growth and productivity. This article covers some of the most vital state-of-the-art information on root senescence.

Senescence in Plants

Senescence, or death, is part of each plant’s life. Plants leverage the senescence of organs or the entire plant to improve productivity and survival. Senescence is a form of programmed cell death (PCD) in plants that is controlled by physiological, biochemical, and genetic factors. It is not synonymous with aging, which is the process of growing old and ultimately leading to death. Senescence occurs after growth is complete and depends on cell viability. Senescence can also occur prematurely due to stress.

Plant senescence is a process in which the cell is broken down in stages, and its contents are remobilized, allowing them to be sent to other sink tissues for reuse.

Subscribe to the CID Bio-Science Weekly article series.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact

The most influential senescence in plants is leaf senescence, followed by whole-plant death.

Leaf senescence is connected to whole plant senescence in monocarpic plants, which complete their entire lifecycle in 1-2 years after one cycle of reproduction. Polycarpic species are perennials that can reproduce multiple times before the whole plant senesces. In these cases, the apical meristem tissue retains its ability to live and divide, thereby maintaining continuous plant growth, though leaf senescence can occur.

There is no evidence that root senescence is correlated with leaf senescence, and the mechanisms that control it operate independently.

Root Senescence

In a 2025 review, Tunc and Wiren state that root senescence can be considered a late developmental stage that occurs after growth stops. Studies show that root senescence depends on plant age rather than tissue age. During the process, the root system does not act as a single organ, but rather as a composition of several organs, because not all root types in a plant die at the same time; instead, they die independently.

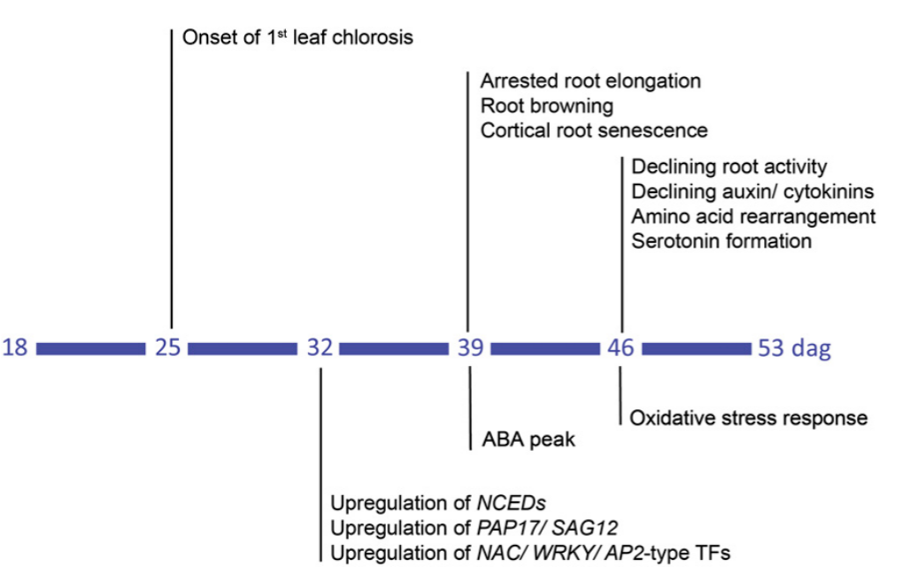

Figure 1: “Temporal sequence of morphological, physiological, and molecular changes with progressing plant age in barley seminal roots. Following onset of chlorosis in the first leaf at 25 d after germination (dag), 32 dag is marked by enhanced expression of transcription factors and genes involved in protein degradation and ABA biosynthesis. At 39 dag, ABA concentrations increase and roots arrest elongation and undergo browning and lesion of the cortex. At 46 dag, decreasing auxin and cytokinin concentrations are accompanied by declining root activity, rearrangements in amino acid metabolism and serotonin formation, as well as altered expression in oxidative stress-related genes,” Liu et al. (2019). (Image credits: DOI: 10.1104/pp.19.00809)

The chronological sequence of processes in root senescence is as follows: altered gene transcription, hormonal signaling, root browning, degeneration of cell layers, changes in hormone levels, declining root activity, and an oxidative stress response (see Figure 1).

Gene expression

Like the senescence control in leaves, the transcription of genes for phytohormone biosynthesis increases along with a spike in the respective hormones, as the root ages. Some genes involved are common to the control of leaf senescence, such as those related to abscisic acid (ABA). For example, in barley, the expression of HvNACs induces ABA biosynthesis genes, thereby boosting ABA levels in roots, which are considered markers of senescence.

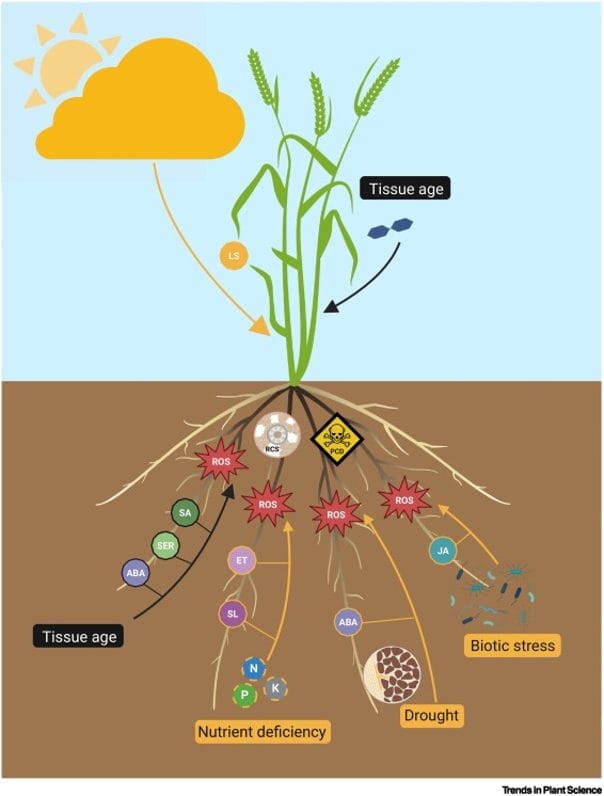

Hormone-generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) will trigger the production of root-specific transcription factors (TFs) to defend against oxidative stress. These TFs cause long-distance signal cascading that could even regulate senescence in shoot organs.

Phytohormones

As in leaf senescence, hormones play a role in root senescence. ABA levels increase in several species, both annual and perennial, during senescence. Exposure to ethylene triggered RCS in barley. In poplar trees, jasmonic acid (JA) levels increased along with ABA during root senescence. These hormones induce oxidative stress by generating ROS such as H2O2, which accelerates senescence and root apices decay.

In addition to phytohormones, mobile RNA and stress-induced peptide hormones produced in the roots are translocated to the xylem, which also regulates the shoots.

Root browning

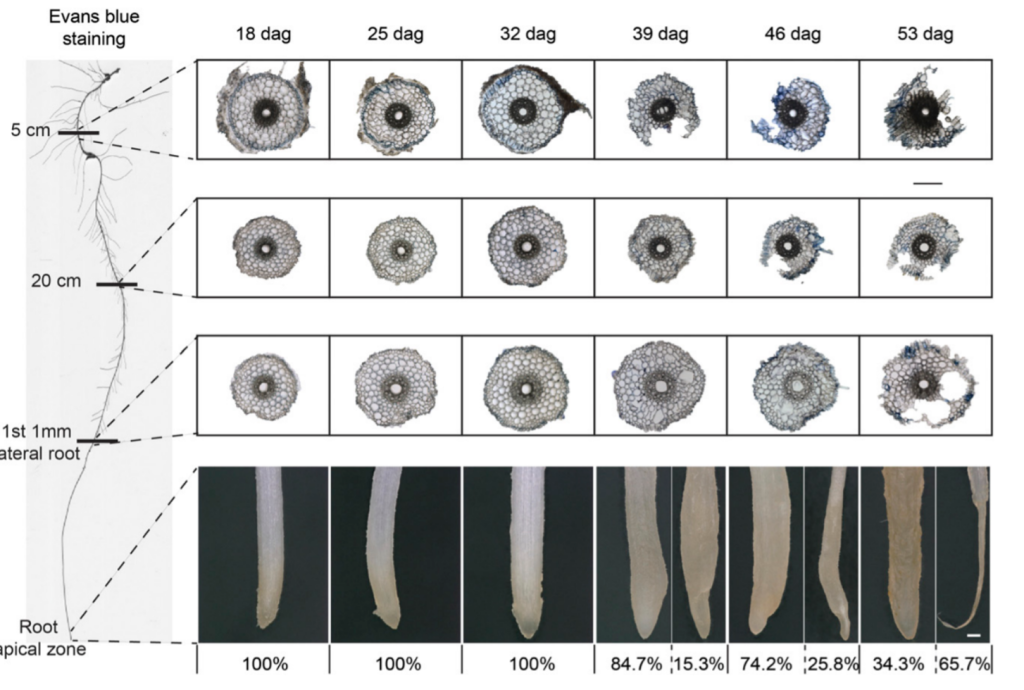

Roots are initially white during the early stages of growth. Due to aging and senescence, the roots begin to turn yellow and brown, as shown in Figure 2. The discoloration starts at the tips and progresses upwards to the shoot. The discoloration occurs in roots of all types and is genetically controlled. In grapes, it is due to tannin accumulation, but the cause is unknown for annuals.

Figure 2: “Structural changes in the seminal root tissue and phenotype of root tips with progressing plant age. Light microscopy of root cross sections at 5 cm below the hypocotyl, 20 cm below the hypocotyl, or at the position where the first lateral root had emerged to a maximum length of 1 mm. Roots of hydroponically grown barley plants were examined weekly from 18 to 53 d after germination (dag). To test membrane integrity, seminal roots were stained with Evans blue. Percentage (%) indicates the abundance of degraded apical root tips. Representative images of root tips with percent values of intact and degraded phenotypes at a given plant age,” Liu et al. (2019). (Image credits: DOI: 10.1104/pp.19.00809)

Root cortical senescence (RCS)

Cell layer degeneration in the outer cortex, which progresses towards the center, produces lesions and disintegration of the outer tissue, as shown in Figure 2. It results in a reduction of the root diameter. The process starts from the tip and proceeds to the root base. The process is controlled by tissue age and plant age, but can also be triggered by nutrient limitations in the soil. RCS is most common in Poaceae species. RCS proceeds fastest in wheat, followed by triticale, barley, rye, and oats. In addition to species, the rate of RCS is also affected by cultivars or biotic stress; see Figure 3. Scientists aim to harness RCS as an adaptive trait to enhance nutrient and water uptake in crops.

Figure 3: “Triggers and drivers of developmental and stress-induced root senescence,” Tunc & Von Wirén (2025). (Image credits. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2025.02.004)

Root activity

RCS results in plasma membrane disintegration, which, in turn, leads to ion leakage and reduced root activity. Loss of cell layers reduces root respiration rates and hydraulic conductance. Age-dependent respiration slowdown is also observed in tree root hairs. Hence, water and nutrient uptake are reduced. For example, RCS can reduce 84-92% of radial nitrate, phosphorus, and water transport in barley.

Root browning, RCs, and reduced root activity are measurable in the fields and used to monitor root senescence.

Nutrient remobilization

There is a lack of evidence of carbon and nutrient remobilization from senescing roots. There is only indirect evidence, due to nutrient and carbon loss from senescing cells and activation of remobilization genes. Scientists are also unsure whether the remobilized nutrients are transported to above-ground sink organs, such as the stem, or if they are leached into the rhizosphere, as a boost to rhizosphere microbial activity follows RCS.

Thus, a genetically controlled sequence of hormonal, metabolic, and anatomical changes brings about tissue decay. Some of the genes involved in leaf senescence are also active during root senescence, but some genes are root-specific.

Senescence of Different Root Types

Roots have two origins: embryonic and post-embryonic. Embryonic roots grow from the radicle present in the seed during germination, and postembryonic roots grow later from root or non-root tissues, such as lateral roots, nodal roots, etc. The pattern in which senescence occurs in these root types also depends on the plant types- dicotyledons and monocots.

Dicotyledons

In dicotyledons, the central primary embryonic axis gives rise to lateral roots and remains active throughout the plant’s life. Tissue PCD is involved in root growth during elongation and secondary growth, as well as in the death of root hairs.

- During root elongation, lateral root cap cells are removed by PCD, allowing the root to extend.

- PCD is the process by which root hairs are terminated within 30 days.

- During root secondary thickening, endodermal cells undergo PCD, allowing radial growth, followed by the formation of the periderm, which reseals and protects the vascular system. This process is age-dependent, but involves the death of the whole tissue.

In contrast to the leaves, where organ senescence starts at the tip and progresses to the base, roots undergo PCD at varying positions in the root systems, even while the tips of the primary and lateral roots can continue to grow.

Monocotyledons

Monocots form a fibrous root system, starting with the production of embryonic, seminal roots, followed by postembryonic nodal roots. Both root types can produce lateral roots, but show no secondary growth, as seen in perennials. However, nodal roots are larger in diameter as they carry large metaxylems. As the plant ages, nodal roots become the primary source of water and nutrients.

Embryonic roots that grow initially are the first to undergo senescence compared to postembryonic nodal roots. For example, in barley, embryonic seminal roots grow at germination and elongate till 39 days after germination (DAG). At this point, root browning begins and marks the transition to senescence (see Figure 2). Barley produced nodal roots at 25 DAG, with most elongation around 46 DAG, and browning began at 53 DAG. So, the nodal roots elongated when the seminal roots started to die.

Importance of Root Senescence

Root senescence has clear benefits for global biogeochemical nutrient and carbon cycling, but benefits to the plants themselves remain unproven.

For the plants

One of the benefits of PCD during leaf senescence is the translocation of metabolites and minerals in the senescence tissue to sinks for recycling.

A breakdown of proteins and amino acids in the roots of barley can be observed with age. However, there was no reduction in protein, as the roots continued to absorb nitrogen. In some species, such as poplar and Arabidopsis roots, bulk protein degradation is facilitated by macro/autophagy as roots age. A subsequent reduction in nitrogen level decreases root elongation and may indicate the transfer of nitrogen away from the roots. However, scientists are unsure if macro/autophagy also occurs after PCD.

Senescence helps plants adjust their biomass allocation as they explore the soil for resources. After the roots are formed, trees can experience nutrient or water deficiencies due to changes in resource availability. In response to soil resource heterogeneity, trees regulate biomass allocation to roots to optimize exploration. This involves the senescence of some roots to redirect resources to other, newly formed roots. In forestry, tree root senescence, which can affect nutrient and water absorption, can impact productivity.

For large-scale nutrient cycling

At larger ecosystem and global scales, tree root senescence influences carbon and nutrient cycling.

In perennial species, approximately 22% of the global net photosynthesis products are allocated to the roots. Root dynamics, specifically the timing of root production, lifespan, and death, influence soil nutrient cycling through root turnover. The dead roots left over after senescence are a significant source of soil carbon, as below-ground sources and processes contribute more to soil carbon sinks than above-ground biomass. Moreover, soil microorganisms break down the roots, releasing nutrients into the soil.

Since each root type’s senescence occurs independently, the death of root hairs and higher-order roots contributes more to root turnover in grassland, shrubs, and tree species. While annuals continuously proliferate post-embryonic roots, including adventitious and lateral roots, throughout the growth season, perennials retain their central axis and laterals for many years and decades.

Another source of root turnover in woody perennial roots is fine roots (diameter <2 mm), which grow to absorb water and nutrients. Fine roots borne on thicker and deeper roots have a longer lifespan than those growing at thinner distal root ends. Fine tree roots have the longest lifespan, followed by those of grasses, shrubs, and forbs. Warmer temperatures and improved soil water availability increased the lifespan of fine roots.

Tree root senescence can be influenced by environmental factors and biotic and abiotic stresses through various mechanisms.

Minirhizotrons to Document Root Senescence

One data collection method that has enhanced our understanding of root senescence is the use of rhizotrons. Minirhizotrons are non-destructive and do not disturb root dynamics once the soil has settled after the transparent, long root tubes are installed, typically within a few weeks. Root imagers can be used to scan the roots growing around the root tubes. CID-BioScience Inc. offers two handheld root imagers: the CI-600 In-Situ Root Imager and the CI-602 Narrow Gauge Root Imager, which capture high-resolution images of unlimited root tubes in crop fields and forests, over several growing seasons.

The software RootSnap! Helps to detect and measure roots. The imagers can detect root discoloration and decay associated with root senescence. Scientists can use these tools to track the root senescence process as often as needed, as more observations and studies are necessary to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the process.

Find out how CID BioScience’s root imagers can help your research.

Sources

Liu, Z., Marella, C. B., Hartmann, A., Hajirezaei, M. R., & von Wirén, N. (2019). An age-dependent sequence of physiological processes defines developmental root senescence. Plant Physiology, 181(3), 993-1007. DOI: 10.1104/pp.19.00809

Schneider, H.M., Lynch, J.P. Functional implications of root cortical senescence for soil resource capture. Plant Soil 423, 13–26 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-017-3533-1

Tunc, C. E., & Von Wirén, N. (2025). Hidden aging: The secret role of root senescence. Trends in Plant Science, 30(5), 553-564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2025.02.004

Wu, C., Wang, Z., & Fan, Z. (2004). Ying yong sheng tai xue bao = The journal of applied ecology, 15(7), 1276–1280.

Related Products

Most Popular Articles

- Transpiration in Plants: Its Importance and Applications

- Leaf Area – How & Why Measuring Leaf Area…

- How to Analyze Photosynthesis in Plants: Methods and Tools

- Plant Respiration: Its Importance and Applications

- The Forest Canopy: Structure, Roles & Measurement

- Stomatal Conductance: Functions, Measurement, and…

- Forest & Plant Canopy Analysis – Tools…

- Root Respiration: Importance and Applications

- The Importance of Leaf Area Index (LAI) in…

- 50 Best Universities for Plant Science